Image copyright Reuters

Image copyright Reuters Nobel Prize winner Tu Youyou helped by ancient Chinese remedy

Tu Youyou has become the first Chinese woman to win a Nobel Prize, for her work in helping to create an anti-malaria medicine. The 84-year-old’s route to the honour has been anything but traditional.

She won the Nobel Prize for medicine, but she doesn’t have a medical degree or a PhD

Tu Youyou attended a pharmacology school in Beijing. Shortly after, she became a researcher at the Academy of Chinese Traditional Medicine.

In China, she is being called the “three noes” winner: no medical degree, no doctorate, and she’s never worked overseas.

She started her malaria research after she was recruited to a top-secret government unit known as “Mission 523”

In 1967, Communist leader Mao Zedong decided there was an urgent national need to find a cure for malaria.

At the time, malaria spread by mosquitoes was decimating Chinese soldiers fighting Americans in the jungles of northern Vietnam.

A secret research unit was formed to find a cure for the illness.

Image copyright AP

Image copyright AP Two years later, Tu Youyou was instructed to become the new head of Mission 523. She was dispatched to the southern Chinese island of Hainan to study how malaria threatened human health.

For six months, she stayed there, leaving her four-year-old daughter at a local nursery.

Ms Tu’s husband had been sent away to work at the countryside at the height of China’s Cultural Revolution, a time of extreme political upheaval.

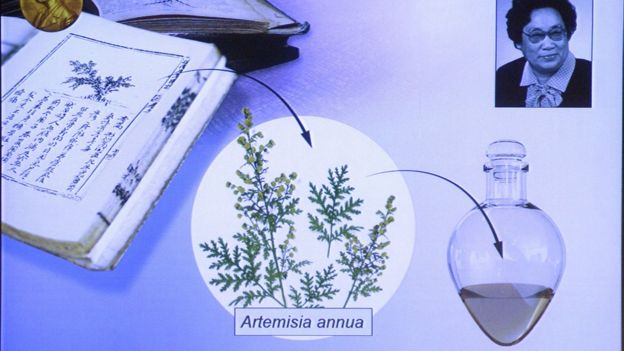

Ancient Chinese texts inspired Tu Youyou’s search for her Nobel-prize winning medicine

Mission 523 pored over ancient books to find historical methods of fighting malaria.

When she started her search for an anti-malarial drug, over 240,000 compounds around the world had already been tested, without any success.

Finally, the team found a brief reference to one substance, sweet wormwood, which had been used to treat malaria in China around 400 AD.

Image copyright AFP/GETTY

Image copyright AFP/GETTY The team isolated one active compound in wormwood, artemsinin, which appeared to battle malaria-friendly parasites.

The team then tested extracts of the compound but nothing was effective in eradicating the drug until Tu Youyou returned to the original ancient text.

After another careful reading, she tweaked the drug recipe one final time, heating the extract without allowing it to reach boiling point.

She first tested her medicine on herself to ensure it was safe

After the drug showed promising results in mice and monkeys, Tu Youyou volunteered to be the first human recipient of the new drug.

“As the head of the research group, I had the responsibility,” she explained to the Chinese media. Shortly after, clinical trials began using Chinese labourers.

Modest mouse or Scene-stealer? You decide

Tu Youyou is typically described in China as a “modest” woman. Her work was published anonymously in 1977, and for decades she received little recognition for her research with Mission 523.

In 2009, Ms Tu published an autobiography looking back on her scientific career. However, she was quickly attacked by some for claiming the spotlight while seemingly ignoring contributions from her colleagues.

Some allege that two other researchers had already targeted the compounds in sweet wormwood before Tu Youyou joined Mission 523.

Image copyright EPA

Image copyright EPA However, she was the one who allegedly consulted the ancient text to study how best to extract the compound for use in medicine.

In any case, Tu Youyou is consistently cited for her drive and passion. One former colleague, Lianda Li, says Ms Tu is “unsociable and quite straightforward”, adding that “if she disagrees with something, she will say it”.

Another colleague, Fuming Liao, who has worked with Tu Youyou for more than 40 years, describes her as a “tough and stubborn woman”.

Stubborn enough to spend decades piecing together ancient texts and apply them to modern scientific practices. The result has saved millions of lives.

Image copyright

Image copyright